The raw and as-insane-as-anticipated first novel from Frank Bill, author of Crimes in Southern Indiana

The Donnybrook is a three-day bare-knuckle tournament held on a thousand-acre plot out in the sticks of southern Indiana. Twenty fighters. One wire-fence ring. Fight until only one man is left standing while a rowdy festival of onlookers—drunk and high on whatever's on offer—bet on the fighters.

Jarhead is a desperate man who'd do just about anything to feed his children. He's also the...

If there’s one thing that’s indisputably true about the characters in Frank Bill’s Donnybrook, it’s that they know how to fight. The author learned a few skills of his own in the notorious hotbed of Asian martial arts that is Southern Indiana. . .

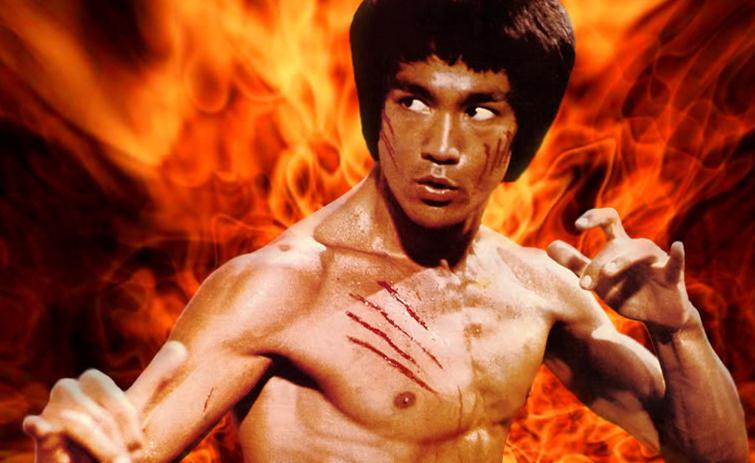

Most Friday and Saturday nights when I was a kid, my parents went out with friends to blow off steam from the workweek. Caught a local jam band at a smoky VFW or American Legion Hall, where they’d dance and guzzle booze into the early AM. I’d stay with my grandparents on their 100-acre farm for the entire weekend. I’d lay spread across the worn cauliflower carpet of the farmhouse’s living room with two pillows tucked beneath my elbows, palms supporting my chin. I’d watch Chinese men in frog-tied tops punch, kick, block, knee, elbow and flip another, their arms springing and snapping like whips on the wood-paneled black and white television with a circular dial of numerals for changing the channels.

From what I recall, the station was out of Louisville, Kentucky, WDRB 41. For a time they televised a late show called Black Belt Theater on Friday nights. Then they moved it to Saturday nights and renamed it Kung Fu Theater. For two hours, they aired these Chinese kung fu flicks made by the Shaw Brothers Studio. I absorbed every movement. In The Chinatown Kid a streetfighter in bellbottom jeans takes on the Asian gangs of San Francisco. In The Five Deadly Venoms, each student wears a mask and has been trained in a secret style: snake, centipede, scorpion or toad. And my favorite, The Master Killer, in which San Te begs at the Shaolin temple’s gates to be trained, waiting in the rain, snow, or heat until he’s accepted and learns the ancient teachings of the monks that were tutored before him.

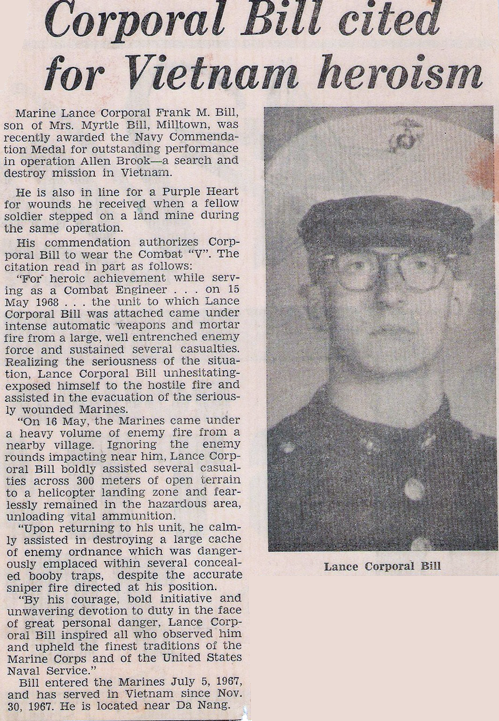

My family had raised me on Clint Eastwood, Sylvester Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenegger. On TV westerns like Bonanza, High Chaparral, The Rifleman, and The Lone Ranger. Men were tough and took no shit. Men like my grandfather, who’d made a living with his hands by working for the town of Corydon during the day as head of the street department but cared for his hound dogs when he arrived home then napped and hunted coon into the late hours of most nights. Men like my father, an ex-Marine who served in the Vietnam War from 68-69, worked Demolition, swept the roads for land mines in Da Nang.

My family had raised me on Clint Eastwood, Sylvester Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenegger. On TV westerns like Bonanza, High Chaparral, The Rifleman, and The Lone Ranger. Men were tough and took no shit. Men like my grandfather, who’d made a living with his hands by working for the town of Corydon during the day as head of the street department but cared for his hound dogs when he arrived home then napped and hunted coon into the late hours of most nights. Men like my father, an ex-Marine who served in the Vietnam War from 68-69, worked Demolition, swept the roads for land mines in Da Nang.

Came home and worked in a tobacco plant for ten years until it went under. Had to start over. Attended night school to become an insurance salesman while bartending on the side. A man who taught me to hunt and fish. Tried to show me the right way to do things but I always managed to do them the wrong way because I wanted to figure things out on my own. And the women were like my mother who was a working class housewife. Had slaved in a chicken factory quartering fowls, just as her mother had. She’d been a cashier and eventually a factory worker in a battery separator plant and then a laborer at United Catalysts.

Those weekends, I spent many mornings gathering eggs from hens in the barn, shucking and tossing feed corn to ducks, helping my grandmother empty the water buckets from a ringer washer after doing laundry. Or, if it was in season, I’d hunt squirrel, rabbit or deer.

Came home and worked in a tobacco plant for ten years until it went under. Had to start over. Attended night school to become an insurance salesman while bartending on the side. A man who taught me to hunt and fish. Tried to show me the right way to do things but I always managed to do them the wrong way because I wanted to figure things out on my own. And the women were like my mother who was a working class housewife. Had slaved in a chicken factory quartering fowls, just as her mother had. She’d been a cashier and eventually a factory worker in a battery separator plant and then a laborer at United Catalysts.

Those weekends, I spent many mornings gathering eggs from hens in the barn, shucking and tossing feed corn to ducks, helping my grandmother empty the water buckets from a ringer washer after doing laundry. Or, if it was in season, I’d hunt squirrel, rabbit or deer.

When I wasn’t hunting, I’d build forts and fires with the blue tip matches my cousin and I stole from our grandmother’s kitchen. Or we corned cars on the valley road from the ears we snagged in the farming crops my grandfather rented out to other farmers.

When I wasn’t hunting, I’d build forts and fires with the blue tip matches my cousin and I stole from our grandmother’s kitchen. Or we corned cars on the valley road from the ears we snagged in the farming crops my grandfather rented out to other farmers.

But on those late weekend nights when my cousin had gone home, my grandfather would be out walking the woods, listening for one of his prized hound dogs to tree a coon and my grandmother’d be in the kitchen with the television blaring while she played Solitaire and chain smoked her Menthol KOOLS—I watched lips mime out of sync with the dubbed-in English. I’d get infused with energy. Leap up and try to mimic the movements of characters. Add the sound effects with my mouth.

In most of the films, there was a little guy who was tough. Got picked on or maybe left for dead by the villain. Then he’d seek out the foremost master in the territory to learn a fighting discipline. But the art was never given. To become a student one had to wait. Show that they were earnest, sincere, that they’d be dedicated. Not abuse the ancient ways. Because to be taught meant the character had to earn it.

And he always did. Through brutal training of the body, mind and spirit. Then the student searched the land for those that wronged him and he kicked their ass. That part was very similar to the American westerns where men settled scores with fists, six shooters and 30/30’s.

Me, I wanted to be like my father. A man who wanted to become a cop in New York but was told he was too short. So he became a Marine. Went through boot camp, did his tour in Nam, came back a more disciplined man. My route would be through fighting. Like the men on my grandparents’ TV, I would learn to wield my hands and feet like weapons. I’d be the little guy who when approached by the chunked up hot head, could paint the walls with his insides.

Or so I thought.

One recess at school—I was around eight or nine, short, boney, blonde-haired and blue-eyed with a gasoline-and-match metabolism that instantly burned through every morsel of nourishment I ingested—a warp-legged kid who was a year older and the size of a baby heifer decided to take me on. My Shaw Brothers kung fu moves didn’t help me at all.

One recess at school—I was around eight or nine, short, boney, blonde-haired and blue-eyed with a gasoline-and-match metabolism that instantly burned through every morsel of nourishment I ingested—a warp-legged kid who was a year older and the size of a baby heifer decided to take me on. My Shaw Brothers kung fu moves didn’t help me at all.

What I remember: Being pushed to the grassy-flat-land, pinned by four times my own heft and laughed at while the other kids stood watching. After school, I told my father what happened, he wasn’t angered in the sense that he knuckled me with fists or bludgeoned me with words. What he did was show me how to curl the digits of my left and right hands into my palms. Clasp the thumb of each onto the outer bend of my index fingers, to squeeze and make a fist. Told me to watch him. He rotated his hips and threw a left punch, then a right. Kept his own hands at his face, showed me how to protect my head. Told me to try it and I did, over and over.

On the playground the next day, when the shoving began, punches were thrown and I was on top of the obese man-child.

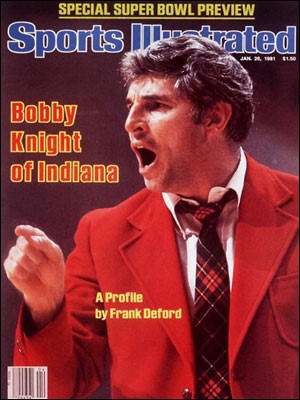

Like most of my buddies, when I entered fifth grade, I went out for the basketball team. To an outsider it’s hard to fathom how basketball pumps through the blood stream on each side of the river in Indiana and Kentucky. When UK or IU play, it’s not uncommon to see fans get so deeply engrained that if their team loses it causes them to upchuck, to be sick for days, to pick fights for days or weeks afterwards over a bad call. Fortunate for me, my parents weren’t like that—my father was and is an IU fan, but he can watch a game and know that when the game is over, win or lose, it’s over. But the rest of the region, basketball runs deep.

Our elementary basketball coach was a wanna-be Bobby Knight. He was a rail with a Frankenstein head and soup bowl tresses. Wore brown-rimmed specs. Always attired in a long-sleeved button-up, pit stains intact, tucked into dress pants, leather belt and slip-ons. His high school ring was a hunk of metal that seemed bigger than his hand. During regular class (he was our math teacher) and at practice, he yelled at us like a drill sergeant.

I made it through the entire season and every practice. I might’ve scored four points. Not that I’d had much floor time or that I was the next Dominique Wilkins. The five who started usually finished. Though there were favorites on the bench, I wasn’t one of them. But still: Indiana Basketball.

I made it through the entire season and every practice. I might’ve scored four points. Not that I’d had much floor time or that I was the next Dominique Wilkins. The five who started usually finished. Though there were favorites on the bench, I wasn’t one of them. But still: Indiana Basketball.

Sometime that year, my mother took me to see The Karate Kid. For me, it was just a movie with a familiar story and not enough fighting, but for my mother, it was the moment she began to understand my fascination not only with martial arts films but also martial arts as a discipline. I’d told her I wanted to study. But there were no schools, or none that she knew of where she or my father could take me between their busy work schedules. My mother worked swing shift at a local factory. My father sold insurance during the day, tended bar at night and played soldier on the weekends in the Army Reserve.

The summer before sixth grade, my mother got word of the Hoosier Hills Karate Club, right in our town. Despite the name, it taught a Korean martial art known as Tae Kwon Do.

The teacher was John King. He was a local caver and construction worker. Had been studying karate since he was my age, was now in his late twenties or early thirties. Tall and muscled from lifting weights, he’d straight brown hair, wore glasses and had a Magnum PI mustache. Drove a red Plymouth Road Runner with a 383. Trained hard but smoked like a diesel engine.

Entering King’s school for that first class, I had butterflies and knots of excitement. The buildup to what I was about to see but also be a part of made me wanna puke. I’d finally be learning those animal and reptile movements I’d watched on those Shaw Brothers films in my grandparents’ living room.

The school was a diminutive warehouse. There was an area for people to sit and watch the classes that were being taught out on a gray concrete workout floor about the size of four or five racquet ball courts. Behind the seating area were plywood walls that’d been sectioned off into men’s and women’s dressing rooms. Bordering the workout area was a carpeted floor with weights, heavy bags and the teacher’s office where the higher ranking students hung out and smoked and listened to our teacher’s stories of fighting in bars and pool halls.

My first class was free. My aunt had accompanied me. I’ve no idea why, other than my mother didn’t want me doing my first class solo.

John instructed us to take off our shoes. Showed us how to bow to the American and Korean flags that hung high from the wood-paneled walls at the front of the creted floor. Hands to our sides. Feet together. Eyes to the flags as we bent at our waist. A gesture of respect but also a lesson; never take your eyes off of your opponent. One had to do this upon entering and exiting the workout area.

John placed us among some other beginners who wore sweat pants and t-shirts. Told us to try and follow as best as we could. In front of us were students in bleach-white uniforms with an American flag patch on the shoulder, red and blue yin/yang patches with a yellow fist in the center on the chest. Men, women and children were arranged by the color of their belts wrapped around their waists and knotted in the center. The colors represented the ranks: white, yellow and green. Purple and brown was the first two rows in the front of the class. At the time, the only black belt was the instructor.

We bowed again. John stood facing everyone. He gave the commands of what we would do. First was a class mantra that I cannot recall. Then everyone kneeled down, bowed their heads and closed their eyes. Took a moment of silence, a meditation to clear the mind, prepare for what was about to take place. Though I didn’t understand that at the time. To me it was like being in church with my grandmother on Sunday mornings when everyone lowered their heads for a silent prayer and I glanced around wondering what people were repenting for.

Everyone stood and John led his students through a series of punches from a posture he called “the horse stance.” From there we began a series of kicks with more punches and chops from other stances. The students’ uniforms snapped and popped as they executed the movements, transitioning from bow stance to cat stance to a sparring stance. Dancing forwards and backwards.

Finally, me and my aunt and the other beginners were given a break and taught about what we’d just done. Shown each different punch and kick. How to execute them properly. Then we sat and watched the different levels perform their hand forms, a combination of techniques; hand strikes, blocks, kicks and stances. Constantly transitioning into one long fighting routine. I sat in awe of all of this, it was just like the movies I’d watched on Kung Fu Theater. I was hooked.

My aunt wasn’t as into it. In a few weeks, she’d be on to skydiving lessons. But my mother enrolled me. Bought me a stiff white uniform and patches. John sold these at the school.

As soon as I got back to school, Frankenstein Head had already caught wind of my training at a martial arts school. Called me into his classroom, wanted to know if I’d planned on playing basketball. Told me it’d be a loss to the team if I didn’t. I wanted to laugh. I was an eleven-year-old bench warmer who’d scored four points over the course of a season. I told him I’d think about it but I never set foot on his court again.

As soon as I got back to school, Frankenstein Head had already caught wind of my training at a martial arts school. Called me into his classroom, wanted to know if I’d planned on playing basketball. Told me it’d be a loss to the team if I didn’t. I wanted to laugh. I was an eleven-year-old bench warmer who’d scored four points over the course of a season. I told him I’d think about it but I never set foot on his court again.

From age eleven on up to sixteen, three days a week I’d train in Tae Kwon Do. Each student was given a silver covered book with the Tae Kwon Do ying yang fist emblem in black on the cover and Korean writing curving around the emblem.

Within that book was a brief history that outlined a conflict between three Korean kingdoms and the creation of a Korean martial arts system. The book was a manual for students to learn the history but also the skills one was taught in class. Such as pressure points. The basic punches, chops, kicks, stances and hand forms.

My parents bought me a weight set that I’d use to maybe put on some size, as I was beyond emaciated. I’d work out at home when I didn’t have class. Filled my father’s green military bag and stuff it with old newspapers, bed sheets and blankets to make my own heavy bag, strung it from our concrete shed’s rafter to kick and punch.

In class, I’d get bruised muscles from other students when sparring. Give them back. Most of the students were two to four years older than I. They were from working class backgrounds. Our parents were farmers, mechanics, truck drivers, beauticians, farm equipment sellers, factory workers and bartenders. They became my closest friends. We’d rent Bruce Lee films, Sonny Chiba films, Chuck Norris karate flicks, Sho Kosugi ninja movies and anything that had martial arts in them on the weekends. Hang out and watch them at one another’s homes.

By this time, I was around fourteen. Was in middle school. Had tested from one rank to the next. Was a brown belt and John, my instructor, was preparing two other students, Todd and Adam, and me for our next rank, first-degree black belt.

By this time, I was around fourteen. Was in middle school. Had tested from one rank to the next. Was a brown belt and John, my instructor, was preparing two other students, Todd and Adam, and me for our next rank, first-degree black belt.

Everything had to be perfect. Forms. Fighting and the breaking of three boards. Because of mine and Adam’s age—I was fourteen and Adam was fifteen—we could choose our strongest technique to break with. Todd, who was sixteen, would have to draw his method from a list of small folded papers, which was much harder. He could draw a hand or a foot technique. But first, we were taken to our teacher’s master’s school in Louisville, Kentucky: Master Choi’s.

None of us were strangers to Master Choi. He was the man everyone tested in front of. I’d been in his presence, testing for from white to yellow, yellow to green, from green to purple and from purple to brown. And now he’d decide our fate. Would watch each of us perform individually. Not a word was spoken. Everyone’s ass was so tight you’d not get a toothpick up it. Choi was known to carry a bamboo stick around with him, use it when a student performed wrong. It sat in a corner for everyone to be aware of. He was about five foot seven, stocky with a thick mop of hair. His uniform was always off-white with an almost purple tent. He was a hard-ass and his voice was loud, foreign and authoritative.

None of us were strangers to Master Choi. He was the man everyone tested in front of. I’d been in his presence, testing for from white to yellow, yellow to green, from green to purple and from purple to brown. And now he’d decide our fate. Would watch each of us perform individually. Not a word was spoken. Everyone’s ass was so tight you’d not get a toothpick up it. Choi was known to carry a bamboo stick around with him, use it when a student performed wrong. It sat in a corner for everyone to be aware of. He was about five foot seven, stocky with a thick mop of hair. His uniform was always off-white with an almost purple tent. He was a hard-ass and his voice was loud, foreign and authoritative.

Luckily none of us got the stick.

Afterwards, we were taken to a restaurant where Adam, Todd and I ate by ourselves and our instructor ate with Choi and he’d tell him YES we were ready or NO we were not.

We were ready.

The testing was held in another state: Nebraska. We were not the only ones testing. This was a huge association, the World Tae Kwon Do Association, so students came from all over the US to test for their black belt or even their next degree of black belt (at the time there were nine degrees of black belt). Cost was around two hundred and fifty for your first degree black. Basically my mother or father’s pay for the week.

Because neither of my parents could afford to get off from work, I rode with Todd and his parents. The building where we tested seemed to be in a rundown area in Omaha, but it was a monstrous gymnasium, maybe an indoor football field.

There were more than a hundred students and we lined up into rows. If memory serves me correctly, there was a master watching and grading over each age group with the direction and assistance of a black belt instructor. These groups were arranged in different squares throughout the gymnasium. So there was constant testing going on all around, all day long.

First, we went through some type of ceremony and a warm-up of kicks and punches. I remember being nervous. I’d always get an upset stomach before testing. It’d pass before I performed. Worse were other kids. Some would get so nervous they’d cry or throw up. Others would break wind in the middle of executing a kick or a punch while all eyes were watching and no one was speaking. Dead silent except for that dreaded sound of escaping gas.

We were broken up into age groups, mine and Adam’s stopped at fifteen. Then you had something like ages sixteen to twenty four; this was Todd’s group. Then twenty-five to thirty and so on. All of the students in my group sat in their ghost-white uniforms. The other groups sat in a different area of the gymnasium, everyone waiting for their names to be called out by the instructor. When my name was called I lined up with several others. Bowed to the commanding instructor. Kept my eyes forward and listened to instruction as to what hand form we’d perform first—one of three brown belt forms, each level had three. In front of us, a master sat at a table with each student’s paperwork spread out before him and he’d grade us. A good many of the masters were in attendance from within the US, this included Master Choi and even the Grandmaster Duk Sung Son (9th degree black belt), the only master who held that rank at the time.

After executing our first three brown belt forms, the instructor asked us to do a surprise form from one of our previous ranks. Then I was paired with one of the other testers and sparred for three minutes, while the seated master graded our fighting technique. Next came the breaking of the three boards in front of a different master. My technique was a flying sidekick. I broke on the first attempt. Then stood, waited for the single comment: PASS! I bowed to the master with an air of confidence but mostly relief.

But the ride home was anything but pleasant. Adam and I passed. Todd did not. The technique Todd drew was one he couldn’t break his boards with and his father was pretty hard on him. Todd would eventually retest and get his black belt, his father’s words just one more rigor in the training.

Me, I kept training and I started to fight in tournaments that were hosted in neighboring states. And as I grew in age and rank I’d place second in a tournament down around Evansville, Indiana, and third at a tournament in Louisville, Kentucky.