One of Vol. 1 Brooklyn's Favorite Fiction Books of 2017, a Literary Hub Staff Favorite Book of 2017, and one of BOMB Magazine's "Looking Back on 2017: Literature" Selections.

"Wondrous . . . [A] sense of the erratic and tangential quality of everyday life—even if it’s displaced into a bizarre, parallel world—drifts off the page, into the world you see, after reading Dear Cyborgs." —Hua Hsu, The New Yorker

In a small Midwestern town, two Asian American boys bond over their outcast status and a...

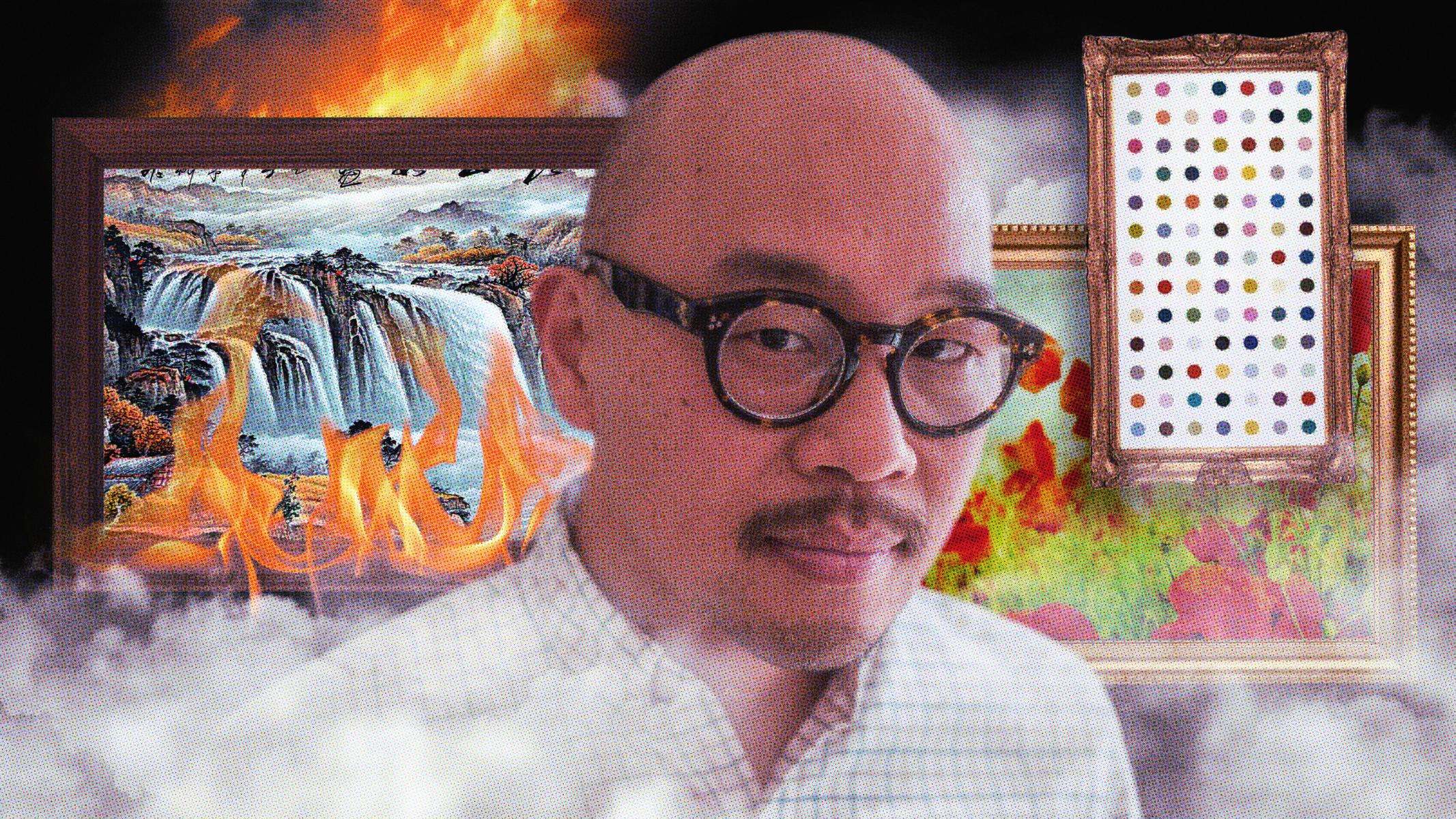

On June 8th at Community Bookstore in Brooklyn, Eugene Lim launched his novel Dear Cyborgs, about which the New Yorker raved, “[Lim’s] writing is confident and tranquil; he has a knack for making everyday life seem strange . . . There’s an intoxicating, whimsical energy on every page.” Eugene spoke with author and FSG editor Jeremy Davies about hopelessness, capitalism, Asian-American literature and more. Check out an edited version of their conversation below.

Jeremy Davies: So, as one bag of anxiety talks to another, the book is full of, as everyone’s heard, a lot of funny stuff, a lot of comic book-y stuff. But one of the things that stood out to me, especially on the second go through, was how well you delineate the anxieties that a lot of us are feeling at this point in time, and perhaps always should be feeling, at this juncture in our culture, politically, as well as in other ways. And the book doesn’t feel angry; it’s more like describing a cage that we’re in and can’t get out, and those are the bars, and that’s the situation. And there’s a line later in the book after a description of what sounds like a Jonas Mekas performance, where one of the characters says just apropos of the performance: “This is what true death would say: not ‘I’m coming for you,’ but ‘You always dwell within me.” So—instead of talking about fun comic book-y stuff, let’s talk about hopelessness and despair.

Eugene Lim: Well, you know, it’s funny, I was surprised that I was writing a somewhat political book, but that particular line is—

JD: It’s more existential, I know, but it’s part and parcel with the character of the book, which is sort of a deadpan acceptance of hopelessness.

EL: Well, acceptance is tougher, but on the very first page of the book there’s this hidden quote from Gramsci, though I am not a well-read leftist, on the leftist theory, but Gramsci, who many of you know, had these prison notebooks, and he wrote this famous quote: “Pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will.” I don’t think that’s his original quote, I actually think he was somebody who made that famous. But that idea of this duality where, you know, he wrote in prison, it wasn’t the best times, and he was a realist, so he was accepting of the despair and the hopelessness, and yet he recognized that he had to be hopeful. And so it’s that contradiction that we live with. A lot of times the left will say, “don’t admit to despair, don’t admit to hopelessness,” because there’s some kind of fear there that the troops will give up and not show up or something. But what I don’t see so often is just an admission of this really hopeless feeling that is in the air, has been in the air. So I think in politics or when you’re actually debating things, you may not be able to admit your despair. But I think in fiction it’s important to confront it; so that’s one accept of it.

JD: Well, the villain of the book, to a certain extent, is capitalism, and it’s a supervillain who takes infinite shapes, and any attack against you make against it can be turned against you. But the book does a really good job of dramatizing that, and also having fun with it, and that’s one of the things that impressed me most when reading it.

EL: There’s this book by Miranda Mellis, who I also really love, she’s a great writer. I wrote about her work, and what I wanted to capture is that we live in this weird time where there’s all these disasters, these slow apocalypses—climate change, economics—on the one hand; on the other hand there’s this weird utopian techno-wonderfulness, supposedly, where we have this ability to have the internet in our pocket, and strangely we talk to people on our screens. So, it’s like, the future is here. And those two things seem initially like they’re in conflict, but one is causing the other. And that, also that conflict, I wanted to respond to.

JD: One of the other things that jumped out at me—this is actually fairly earlier in the book, and I won’t add to your reading and try to compete with you, but this jumped out at me quite a bit—the section where one of the characters—the book actually has several narrators—is speaking about his failed attempt to write a novel, and he says,

It wasn’t writer’s block then, not exactly. At the time I knew what was expected. “What was expected was a slightly modified coming of-age novel that traded on my Korean-American identity. Something not too obviously an assimilation tale—and above all clever—yet also something not too much a deviation from that sellable idea, so that the marketplace of culture could easily absorb my story without being too discomfited. Even if no one had said this aloud, to me it was clear as day that this was the assignment. “And I was willing to do it! It wasn’t ethics that seemed to make the job impossible, but rather, I think, an underdeveloped sense of humor. I couldn’t laugh it off. I couldn’t get in the right mood. To sell that subject, which, to overgeneralize, is one step past the melodrama and pathos of the first generation’s suffering. That is, in order to sell the second generation’s schizophrenia and double-agenthood, one needs to pepper the thing with jokes, so you can say, See, I’m no victim, not only.

EL: I think that there’s some great shifts that are happening, in terms of Asian-American lit, and I went to Dr. Loonam’s class—he’s our head high school teacher—a couple weeks ago, and I talked about Asian-American lit. And I realized, I’ve come to realize, there is something that impacted my life a lot that I never really thought about, which is immigration law. There was this big change in the law in ’65—which law has always been, in this country, racist—but at that point there was this big legislation that allowed people to come in from Latin America and Asia and Africa and non-Western countries. Congress at the time didn’t think that it was going to be a big deal. But it turned out to be a big deal, and this wave of immigrants came through, including my parents. And, so, what I told the kids in this class, is that when I was their age—17 or18 years old—and I met someone like me—in their forties—that person would speak with an accent. In Ohio, at least. When I went to California, things were different. But when I moved to California as a young person, and I met someone, my parents’ age or older, and they didn’t speak with an accent, I was blown away. Because there was deeper immigration on the coasts. But in Ohio, everyone I met over forty had an accent. That was a big difference.

So, I was watching the Hasan Minhaj comedy thing on Netflix, which before it came on my feed I had no idea who this was, really, but maybe you all do. And I like the show. If any of you know what I’m talking about, there’s this comedy special on Netflix. It’s a very tightly written show about an Asian-American guy and his high school life. It’s supposed to be a comedy but I wept through the whole thing. I seriously did, because it’s about this emasculation of his identity in high school. Not to get into it too much. So, I started Googling Hasan Minhaj, and I saw this—this is a little digression—I saw this interview with him on the radio, and with these morning DJs. And the morning DJs were kind of slangy, and they would say, “Man, you’re poppin’! And Aziz Ansari is poppin’, and it’s amazing, all of these Indian-American artists are popping. Why is it, it’s weird that it’s all happening right now.” And I thought, oh, I know the answer. It’s because Hart-Celler, 1965—because my parents came over, in this brain drain, and those people’s parents came over in this brain drain, after ’65. And then their kids are now in their thirties, forties, and fifties, and it’s the first time that they’re coming into places of power. When we talk about Fresh Off the Boat—whatever you think of the book, there was the TV show—it was the first TV show with an Asian-American cast in fifteen years. The reason it was made possible is not because the writer is very funny, which he is, but the showrunner, and the exec that gave it the green light at the studios, they were all Asian-American, and they were in the right place at the right time.

Kurt Vonnegut makes this joke, which I thought was very funny—I tried it on the high school kids but they didn’t think it was that funny: “True horror is when you wake up and your graduating class is running the country.” [Laughter] See, you guys get it. Because you start getting older, and, all of a sudden, your cardiologist is your age, or your congressman is your age. But it takes a while for people to come to power, so you get these editors and people coming to power, and English is their first language, and there’s this assimilation thing that’s happening, and you get this big change. There’s this big change from the first to the second generation. I don’t think it’s recognized exactly how these forces of history work, because we don’t think they make a difference. Ning and I would go—Ning is an old friend, we grew up in Ohio. We would come to see things in New York, when we first got here in the late ‘90s. We would look around, and there were no Asian kids. And I would go, “It’s New York City, why are we the only Asian people in the room?” And that is changing, and it has changed. Those rooms are changing, little bit by little bit. But not until recently, and not until people have come into positions of power. I forgot the question now. [Laughter]