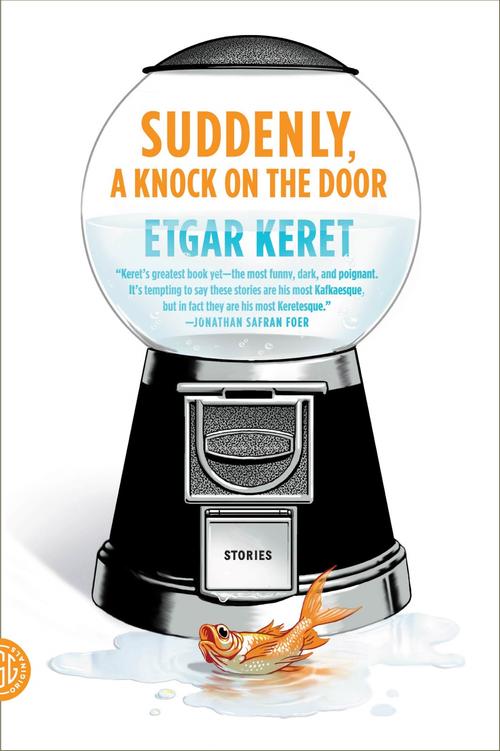

Bringing up a child, lying to the boss, placing an order in a fast-food restaurant: in Etgar Keret's new collection, daily life is complicated, dangerous, and full of yearning. In his most playful and most mature work yet, the living and the dead, silent children and talking animals, dreams and waking life coexist in an uneasy world. Overflowing with absurdity, humor, sadness, and compassion, the tales in Suddenly, a Knock on the Door establish Etgar Keret—declared a "genius" by The New York Times—as one of the most original writers of his generation.

Paperback, FSG Originals, 2012

read an excerptAn excerpt from Suddenly, a Knock on the Door

Suddenly, a Knock on the Door

“Tell me a story,” the bearded man sitting on my living-room sofa commands. The situation, I must say, is anything but pleasant. I’m someone who writes stories, not someone who tells them. And even that isn’t something I do on demand. The last time anyone asked me to tell him a story, it was my son. That was a year ago. I told him something about a fairy and a ferret—I don’t even remember what exactly—and within two minutes he was fast asleep. But the situation is fundamentally different. Because my son doesn’t have a beard, or a pistol. Because my son asked for the story nicely, and this man is simply trying to rob me of it.

I try to explain to the bearded man that if he puts his pistol away it will only work in his favor, in our favor. It’s hard to think up a story with the barrel of a loaded pistol pointed at your head. But the guy insists. “In this country,” he explains, “if you want something, you have to use force.” He just got here from Sweden, and in Sweden it’s completely different. Over there, if you want something, you ask politely, and most of the time you get it. But not in the stifling, muggy Middle East. All it takes is one week in this place to figure out how things work—or rather, how things don’t work. The Palestinians asked for a state, nicely. Did they get one? The hell they did. So they switched to blowing up kids on buses, and people started listening. The settlers wanted a dialogue. Did anyone pick up on it? No way. So they started getting physical, pouring hot oil on the border patrolmen, and suddenly they had an audience. In this country, might makes right, and it doesn’t matter if it’s about politics, or economics or a parking space. Brute force is the only language we understand.

Sweden, the place the bearded guy made aliya from, is progressive, and is way up there in quite a few areas. Sweden isn’t just ABBA or IKEA or the Nobel Prize. Sweden is a world unto itself, and what ever they have, they got by peaceful means. In Sweden, if he’d gone to the Ace of Base soloist, knocked on her door, and asked her to sing for him, she’d have invited him in and made him a cup of tea. Then she’d have pulled out her acoustic guitar from under the bed and played for him. All this with a smile! But here? I mean, if he hadn’t been fl ashing a pistol I’d have thrown him out right away. Look, I try to reason. “ ‘Look’ yourself,” the bearded guy grumbles, and cocks his pistol. “It’s either a story or a bullet between the eyes.” I see my choices are limited. The guy means business. “Two people are sitting in a room,” I begin. “Suddenly, there’s a knock on the door.” The bearded guy stiffens, and for a moment I think maybe the story’s getting to him, but it isn’t. He’s listening to something else. There’s a knock on the door. “Open it,” he tells me, “and don’t try anything. Get rid of whoever it is, and do it fast, or this is going to end badly.”

The young man at the door is doing a survey. He has a few questions. Short ones. About the high humidity here in summer, and how it affects my disposition. I tell him I’m not interested but he pushes his way inside anyway.

“Who’s that?” he asks me, pointing at the bearded guy. “That’s my nephew from Sweden,” I lie. “His father died in an avalanche and he’s here for the funeral. We’re just going over the will. Could you please respect our privacy and leave?” “C’mon, man,” the pollster says, and pats me on the shoulder. “It’s just a few questions. Give a guy a chance to earn a few bucks. They pay me per respondent.” He fl ops down on the sofa, clutching his binder. The Swede takes a seat next to him. I’m still standing, trying to sound like I mean it. “I’m asking you to leave,” I tell him. “Your timing is way off.” “Way off, eh?” He opens the plastic binder and pulls out a big revolver. “Why’s my timing off? ’Cause I’m darker? ’Cause I’m not good enough? When it comes to Swedes, you’ve got all the time in the world. But for a Moroccan, for a war veteran who left pieces of his spleen behind in Lebanon, you can’t spare a fucking minute.” I try to reason with him, to tell him it’s not that way at all, that he’d simply caught me at a delicate point in my conversation with the Swede. But the pollster raises his revolver to his lips and signals me to shut up. “Vamos,” he says. “Stop making excuses. Sit down over there, and out with it.” “Out with what?” I ask. The truth is, now I’m pretty uptight. The Swede has a pistol too. Things might get out of hand. East is east and west is west, and all that. Different mentalities. Or else the Swede could lose it, simply because he wants the story all to himself. Solo. “Don’t get me started,” the pollster warns. “I have a short fuse. Out with the story—and make it quick.” “Yeah,” the Swede chimes in, and pulls out his piece too. I clear my throat, and start all over again. “Three people are sitting in a room.” “And no ‘Suddenly, there’s a knock on the door,’ ” the Swede announces. The pollster doesn’t quite get it, but plays along with him. “Get going,” he says. “And no knocking on the door. Tell us something else. Surprise us.”

I stop short, and take a deep breath. Both of them are staring at me. How do I always get myself into these situations? I bet things like this never happen to Amos Oz or David Grossman. Suddenly there’s a knock on the door. Their gaze turns menacing. I shrug. It’s not about me. There’s nothing in my story to connect it to that knock. “Get rid of him,” the pollster orders me. “Get rid of him, whoever it is.” I open the door just a crack. It’s a pizza delivery guy. “Are you Keret?” he asks. “Yes,” I say, “but I didn’t order a pizza.” “It says here Fourteen Zamenhoff Street,” he snaps, pointing at the printed delivery slip and pushing his way inside. “So what,” I say, “I didn’t order a pizza.” “Family size,” he insists. “Half pineapple, half anchovy. Prepaid. Credit card. Just gimme my tip and I’m outta here.” “Are you here for a story too?” the Swede interrogates. “What story?” the pizza guy asks, but it’s obvious he’s lying. He’s not very good at it. “Pull it out,” the pollster prods. “C’mon, out with the pistol already.” “I don’t have a pistol,” the pizza guy admits awkwardly, and draws a cleaver out from under his cardboard tray. “But I’ll cut him into julienne strips unless he coughs up a good one, on the double.”

The three of them are on the sofa—the Swede on the right, then the pizza guy, then the pollster. “I can’t do it like this,” I tell them. “I can’t get a story going with the three of you here and your weapons and all that. Go take a walk around the block, and by the time you get back, I’ll have something for you.” “The asshole’s gonna call the cops,” the pollster tells the Swede. “What’s he thinking, that we were born yesterday?” “C’mon, give us one and we’ll be on our way,” the pizza guy begs. “A short one. Don’t be so anal. Things are tough, you know. Unemployment, suicide bombings, Iranians. People are hungry for something else. What do you think brought law- abiding guys like us this far? We’re desperate, man, desperate.”

I clear my throat and start again. “Four people are sitting in a room. It’s hot. They’re bored. The air conditioner’s on the blink. One of them asks for a story. The second one joins in, then the third . . .” “That’s not a story,” the pollster protests. “That’s an eyewitness report. It’s exactly what’s happening here right now. Exactly what we’re trying to run away from. Don’t you go and dump reality on us like a garbage truck. Use your imagination, man, create, invent, take it all the way.”

I nod and start again. “A man is sitting in a room, all by himself. He’s lonely. He’s a writer. He wants to write a story. It’s been a long time since he wrote his last story, and he misses it. He misses the feeling of creating something out of something. That’s right—something out of something. Because something out of nothing is when you make something up out of thin air, in which case it has no value. Anybody can do that. But something out of something means it was really there the whole time, inside you, and you discover it as part of something new, that’s never happened before. The man decides to write a story about the situation. Not the political situation and not the social situation either. He decides to write a story about the human situation, the human condition. The human condition the way he’s experiencing it right now. But he draws a blank. No story presents itself. Because the human condition the way he’s experiencing it right now doesn’t seem to be worth a story, and he’s just about to give up when suddenly . . .” “I warned you already,” the Swede interrupts me. “No knock on the door.” “I’ve got to,” I insist. “Without a knock on the door there’s no story.” “Let him,” the pizza guy says softly. “Give him some slack. You want a knock on the door? Okay, have your knock on the door. Just so long as it brings us a story.”