Jessica Friedmann navigates her recovery from postpartum depression in a wide-ranging collection of personal essays

Things That Helped is a memoir in essays, detailing the Australian writer Jessica Friedmann’s recovery from postpartum depression. In each essay she focuses on a separate totemic object—from pho to red lips to the trans musician Anohni—to tell a story that is both deeply personal and culturally resonant. Drawing on critical theory, popular culture, and her own experience,...

MARIBYRNONG

In the beginning there was the river, wending its way around the top of the suburb, then snaking out protectively toward the south. The water was deep and cold and full of silt, and in the months after I had my baby I would often dream of going down to drown myself in it.

At dusk the river’s parklands were beginning to empty out, the cyclists and joggers wary of the cold and the settling night. Old men who squatted on their heels reeled their fishing lines in, carrying their lures home in scrubbed out paint buckets. Soon it would be dark; soon a cloistering silence would descend on the leaves and grass, broken only by the rustle of the wind and the steady drone of the highway, as persistent as seawater or the beat of a heart.

PHO

As we inch toward Christmas, and the weather gets hotter and drier, each week of viability feeling like a clandestine accomplishment, the nausea becomes more intense. I find out, for the first time, about food aversions, which are much stronger and more visceral than any of my cravings. The provisions I had thought would carry me through my pregnancy—licorice and pickles and dark chocolate and potato chips—are too oily, too salty, too acidic by turns. The only thing I want to eat is pho.

RED LIPS

I have worn lipstick since long before he was born; every day, for many years. I can’t remember, though, when habit became ritual. I feel as though if I could, if I could pin down the moment that commenced a daily ceremony, I might demarcate between girl and woman with clear, metaphoric ease. But when and how do you become a woman? It is a long, raw process that doesn’t seem to end.

SWANLIGHT, TURNING

Listening to Anohni sing, I am astonished to realize that there was a time that I had not yet heard her. It is one of those moments of peripeteia, of vertigo, of something taking flight. I find myself in tears, not just at the beauty of her voice, but at the sense that I have found, as Anne Shirley would say, a “kindred spirit”—not a girlish, plump Diana, but a grown woman whose longing is shot through with loneliness and pain.

Nobody tells you, as a child, that your initiation into womanhood might come at the price of a craving for misuse and violence; that you can protect yourself from others, but that nobody can protect you from yourself.

SKYWHALE

I begin to fall in love with the whale and her maternal uplift. With ten pendulous teats she could nourish a city, but instead she has broken free of the demands of her invisible children and soars above them, benevolent, always moving upward. That idea of lightness stays with me for days.

CENTER STAGE, FIVE DANCES, AND OTHER DANCE ON-SCREEN

I wrap myself in bed linen until there is no part of me that is not smothered and swaddled. It is safe to be entirely ensconced in blankets. On-screen, the dancers are almost bare, sheathed in thin leotards as they pirouette and chassé across the stage. I watch them, mesmerized, as the weight of my limbs and the weight of the blankets sink me into the softness of the mattress, the flannel sheets.

ALTERED NIGHT

I am tangling with a new, unspoken etiquette: the sense that the polite thing to do is put my head down, stay home, attend to my child, and reappear after a few years, when my life more easily molds to the pattern of six p.m. book launches and countless hours of unpaid arts-organization overtime—just disappear, and come back as though nothing has changed me or changed the pace of my life. I am too tired to rock the boat, but it is difficult making work this way, and, above everything else, it is lonely.

WEAVING

When I first begin to lose my connection to words, I don’t believe that anything serious is going on. Temporary aphasia is a fairly common symptom of pregnancy, part of the catchall “baby brain” that excuses clumsiness, forgetfulness, teariness.

Language is my bread and butter, but I am lucky: I am working at a magazine where the editor and I are so silently sympathetic that sometimes we can go entire days without real conversation. If I drop a word, it is usually only into his outstretched hand.

Patrick is gracious, but I catch him looking faintly quizzical at times and recall myself to myself in the middle of a sentence, one in which I’ve unconsciously substituted a poorer word for the right one, skipping over meaning for the closest possible sound.

“I did it again, didn’t I?” I ask, and he has to say yes.

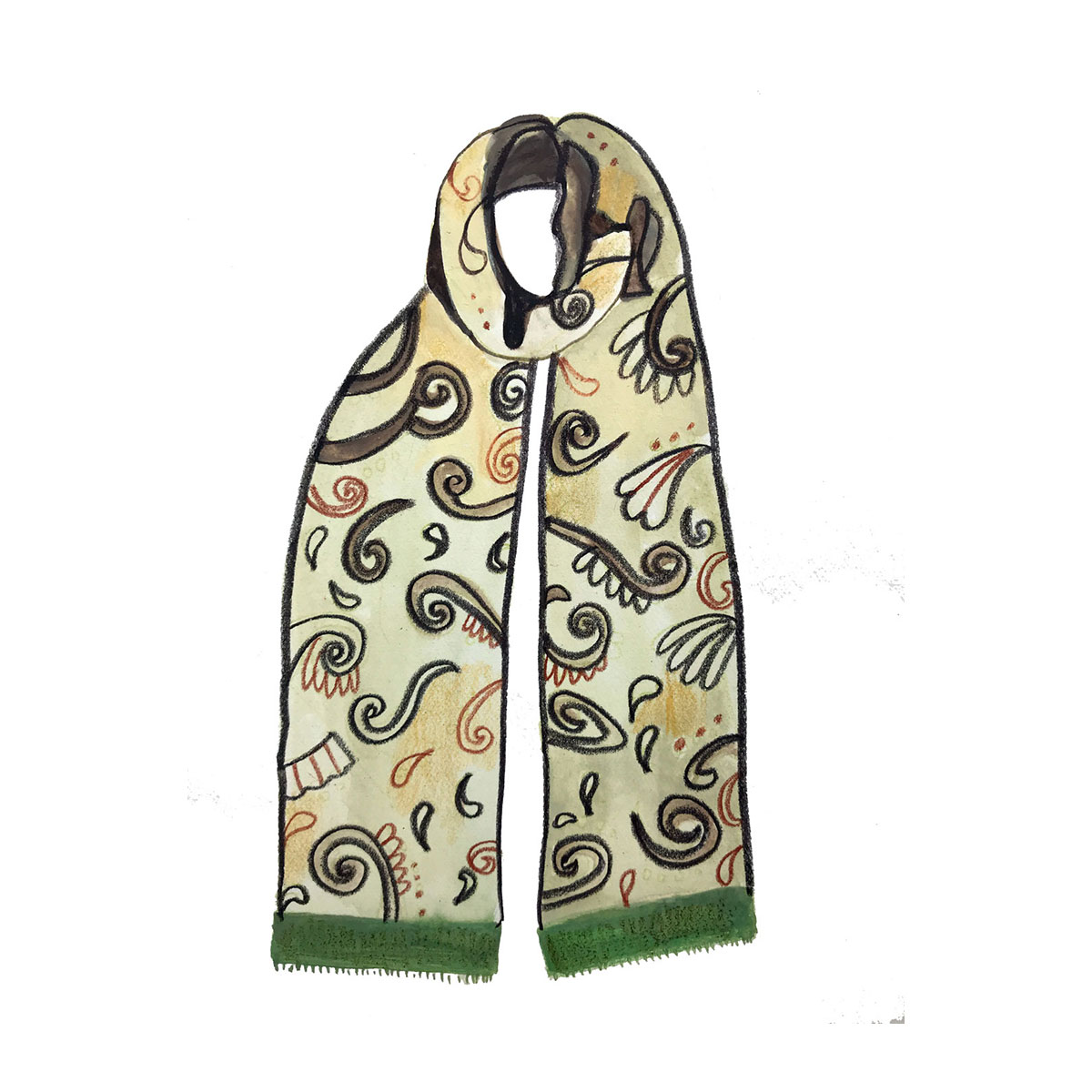

VIRGINIA’S SCARF

In the months after Virginia died, I often thought I saw her on the street. Walking Owen to day care, we would pass a woman in her sixties or seventies, and I would catch a glimpse of nautical stripes, or large gold earrings, or a dark bob streaked with gray, and for a second Virginia’s face would superimpose itself on the face of a perfect stranger. After death, memory begins to ossify, fixing a person in time and space, but Virginia, in my mind, had long been static; unbending and unyielding, not much given to change. That is how I always thought of her—impervious— and maybe that was why she could appear so strikingly on the faces of other women.

WALKING

After Owen is born, and as I sink swiftly into depression, and am no longer fooling anybody, I walk all over Footscray, pushing the baby and narrating my steps, as suggested by the hospital psychologist; it is supposed to ground you to say the things you are doing at the moment that you are doing them, to narrow your scope to the immediacy of voice and breath. What I think about instead is the land as it must have been just a whisper ago, before the boat carrying my father arrived, before the boat carrying my mother’s ancestors arrived. I wonder what songlines I am tracing as I walk around the river, comforting myself with the fact that I am not fit to carry them anyway, and envy the pakeha women at the park, white New Zealanders, for their casual naming of things to their children: paihamu, rakiraki, kikorangi.

RINGS

I have never thought that I would bother with marriage; if I have any hazily defined plans, they involve wafting around Paris or Berlin, writing a novel, having affairs with older men, or possibly loving someone, moving in with them, having a child together; marriage hasn’t seemed necessary. Even now I cannot articulate why I want it. I want it even though I know, intellectually, that a marriage certificate is simply a piece of paper. I know the history of the institution, how oppressive it has been to women, how oppressive it is now to my queer friends who want, if not the institution itself, then at least the right to participate in it. But these things pale before an urge that comes from nowhere, and is as relentless and compelling as the urge to have a baby soon will be.

AINSLIE

The house was nestled more or less at the foot of a mountain, Mount Ainslie. The name Canberra is supposed to come from a Ngunnawal word, kambera, a meeting place. Much more likely it derives from nganbira, the hollow between two breasts, the twin uprising swells of Mount Ainslie and Black Mountain. I like this story better, for the space between the earth’s breasts must be more or less directly above her heart. Slow and lean, the trees here rustle in hot north wind, trading secrets in a leaf language of wattle and gum.